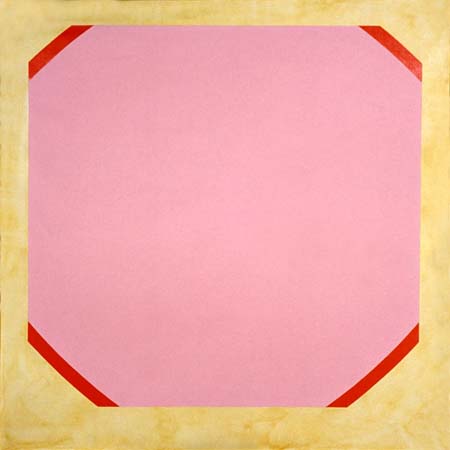

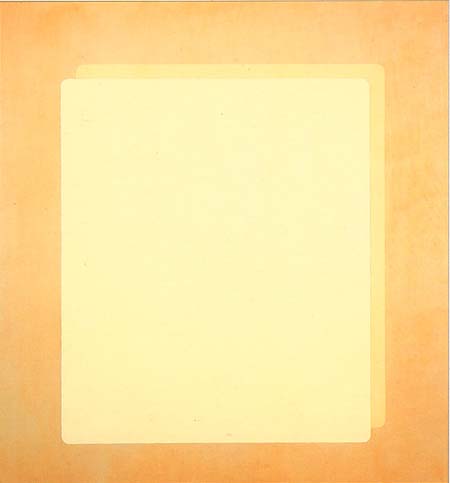

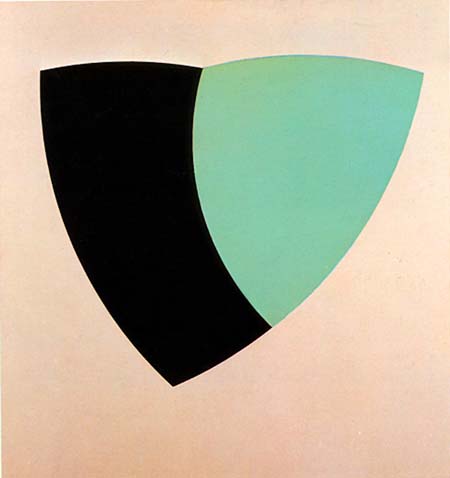

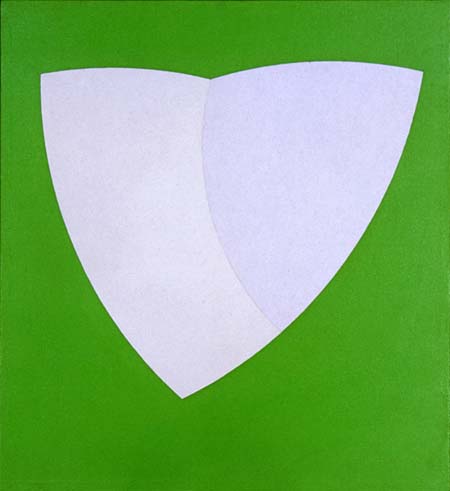

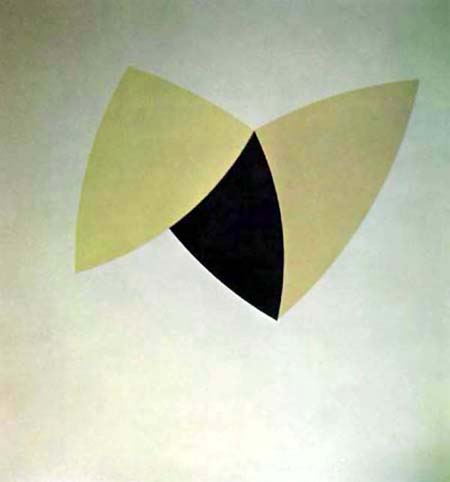

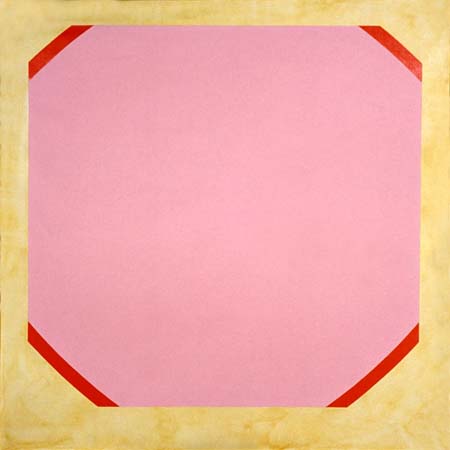

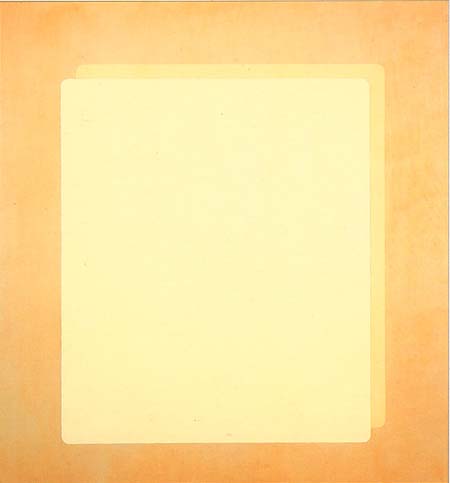

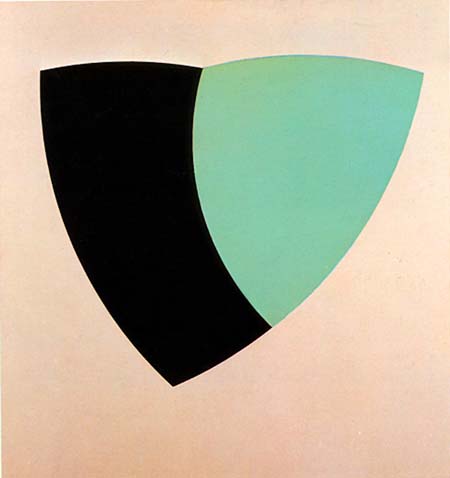

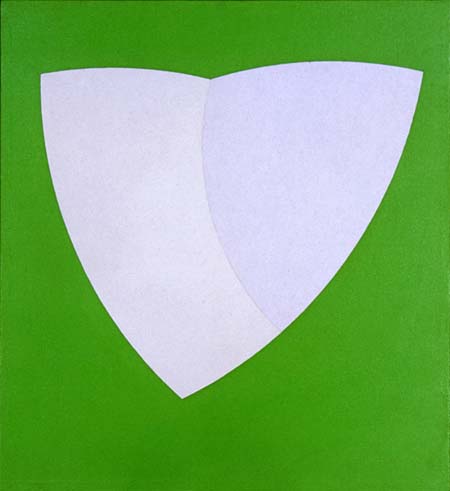

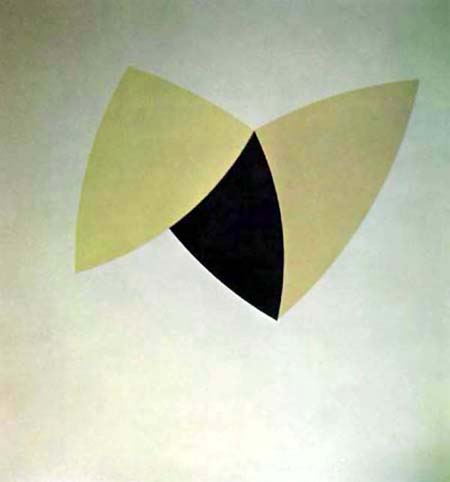

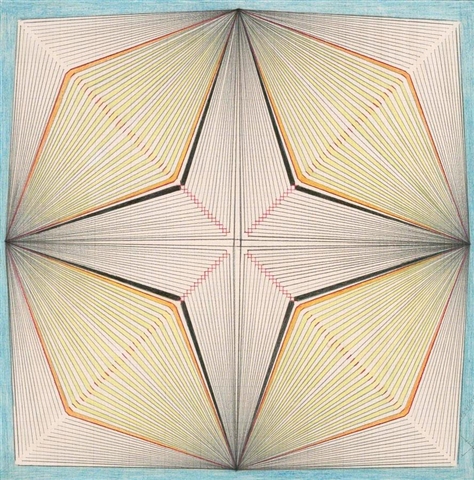

Darby Bannard – Paintings 1960-1970

Darby Bannard – Paintings 1960-1970

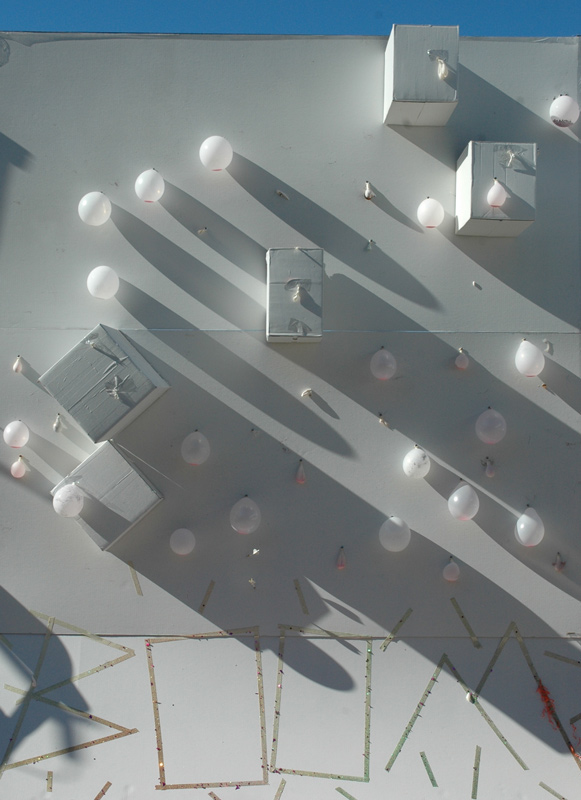

Sculpture work by Courtney Price 2011

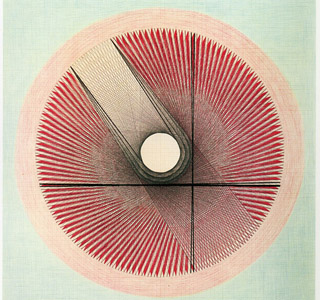

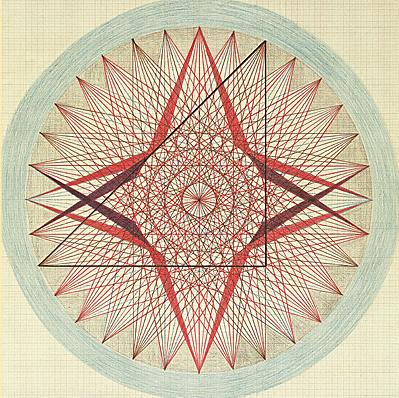

Emma Kunz

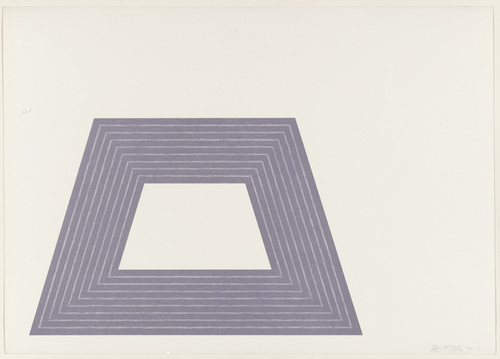

Frank Stella

De Wain Valentine

Valentine spent his childhood in Colorado. His family worked in hard rock mining and as a child he would visit the mines, and started collecting and polishing his found objects. When he started polishing the stones and specifically the crystals, he was led to the observation and experience of hard objects having translucency and transparency.

Norman Mercer

Phillip Low

By this art you may contemplate the variation of the 23 letters . . . – The Anatomy of Melancholy, Part 2, Sect. II, Mem. IV.

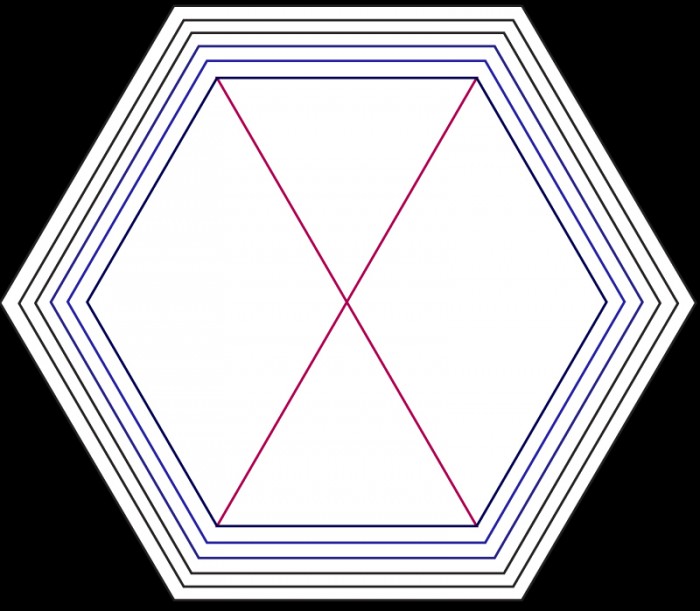

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps an infinite, number of hexagonal galleries, with enormous ventilation shafts in the middle, encircled by very low railings. From any hexagon the upper or lower stories are visible, interminably. The distribution of the galleries is invariable. Twenty shelves – five long shelves per side – cover all sides except two;their height, which is that of each floor, scarcely exceeds that of an average librarian. One of the free sides gives upon a narrow entrance way, which leads to another gallery, identical to the first and to all the others. To the left and to the right of the entrance way are two miniature rooms. One allows standing room for sleeping; the other, the satisfaction of fecal necessities. Through this section passes the spiral staircase, which plunges down into the abyss and rises up to the heights. In the entrance way hangs a mirror, which faithfully duplicates appearances. People are in the habit of inferring from this mirror that the Library is not infinite (if it really were, why this illusory duplication?); I prefer to dream that the polished surfaces feign and promise infinity . . .Light comes from some spherical fruits called by the name of lamps. There are two, running transversally, in each hexagon. The light they emit is insufficient, incessant.

Like all men of the Library, I have traveled in my youth. I have journeyed in search of a book, perhaps of the catalogue of catalogues; now that my eyes can scarcely decipher what I write, I am preparing to die a few leagues from the hexagon in which I was born. Once dead, there will not lack pious hands to hurl me over the banister; my sepulchre shall be the unfathomable air: my body will sink lengthily and will corrupt and dissolve in the wind engendered by the fall, which is infinite. I affirm that the Library is interminable. The idealists argue that the hexagonal halls are a necessary form of absolute space or, at least, of our intuition of space. They contend that a triangular or pentagonal hall is inconceivable. (The mystics claim that to them ecstasy reveals a round chamber containing a great book with a continuous back circling the walls of the room; but their testimony is suspect; their words, obscure. That cyclical book is God.) Let it suffice me, for the time being, to repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere whose consummate center is any hexagon, and whose circumference is inaccessible.

Five shelves correspond to each one of the walls of each hexagon; each shelf contains thirty-two books of a uniform format; each book is made up of four hundred and ten pages; each page, of forty lines; each line, of some eighty black letters. There are also letters on the spine of each book; these letters do not indicate or prefigure what the pages will say. I know that such a lack of relevance, atone time, seemed mysterious. Before summarizing the solution (whose disclosure, despite its tragic implications, is perhaps the capital fact of this history), I want to recall certain axioms. The first: The Library exists ab aeterno. No reasonable mind can doubt this truth, whose immediate corollary is the future eternity of the world. Man, the imperfect librarian, may be the work of chance or of malevolent demi urges; the universe, with its elegant endowment of shelves, of enigmatic volumes, of indefatigable ladders for the voyager, and of privies for the seated librarian, can only be the work of a god. In order to perceive the distance which exists between the divine and the human,it is enough to compare the rude tremulous symbols which my fallible hand scribbles on the end pages of a book with the organic letters inside: exact, delicate, intensely black, inimitably symmetric.The second: The number of orthographic symbols is twenty-five.

This bit of evidence permitted the formulation, three hundred years ago, of a general theory of the Library and the satisfactory resolution of the problem which no conjecture had yet made clear: the formless and chaotic nature of almost all books. One of these books, which my father saw in a hexagon of the circuit number fifteen ninety-four, was composed of the letters MCV perversely repeated from the first line to the last. Another, very much consulted in this zone, is a mere labyrinth of letters, but on the next-to-the-last page, one may read O Time your pyramids. As is well known: for one reasonable line or one straightforward note there are leagues of insensate cacaphony, of verbal farragoes and incoherencies. (I know of a wild region whose librarians repudiate the vain superstitious custom of seeking any sense in books and compare it to looking for meaning in dreams or in the chaotic lines of one’s hands. . . They admit that the inventors of writing imitated the twenty-five natural symbols, but they maintain that this application is accidental and that books in themselves mean nothing. This opinion- we shall see – is not altogether false.) For a long time it was believed that these impenetrable books belonged to past or remote languages.It is true that the most ancient men, the first librarians, made use of a language quite different from the one we speak today; it is true that some miles to the right the language is dialectical and that ninety stories up it is incomprehensible. All this, I repeat, is true; but four hundred and ten pages of unvarying MCVs do not correspond to any language, however dialectical or rudimentary it might be. Some librarians insinuated that each letter could influence the next, and that the value of MCV on the third line of page 71 was not the same as that of the same series in another position on another page; but this vague thesis did not prosper. Still other men thought in terms of cryptographs; this conjecture has come to be universally accepted, though not in the sense in which it was formulated by its inventors.

Five hundred years ago, the chief of an upper hexagon came upon a book as confusing as all the rest but which contained nearly two pages of homogenous lines. He showed his find to an ambulant decipherer, who told him the lines were written in Portuguese. Others told him they were in Yiddish. In less than a century the nature of the language was finally established: it was a Samoyed-Lithuanian dialect of Guarani, with classical Arabic inflections.

The contents were also deciphered: notions of combinational analysis, illustrated by examples of variations with unlimited repetition. These examples made it possible for a librarian of genius to discover the fundamental law of the Library. This thinker observed that all the books, however diverse, are made up of uniform elements: the period, the comma, the space, the twenty-two letters of the alphabet. He also adduceda circumstance confirmed by all travelers: There are not, in the whole vast Library, two identical books. From all these incontrovertible premises he deduced that the Library is total and that its shelves contain all the possible combinations o££ the twenty-odd orthographic symbols (whose number, though vast, is not infinite); that is, everything which can be expressed, in all languages. Everything is there: the minute history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalogue of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, a demonstration of the fallacy of these catalogues, a demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnosticgospel of Basilides, the commentary on this gospel, the commentary on the commentary of this gospel, the veridical account of your death, a version of each book in all languages, the interpolation sof every book in all books.

When it was proclaimed that the Library comprised all books, the first impression was one of extravagant joy. All men felt themselves lords of a secret, intact treasure. There was no personal or universal problem whose eloquent solution did not exist -in some hexagon. The universe was justified, the universe suddenly expanded to the limitless dimensions of hope. At that time there was much talk of the Vindications: books of apology and prophecy, which vindicated for all time the actions of every man in the world and established a store of prodigious arcana for the future.Thousands of covetous persons abandoned their dear natal hexagons and crowded up the stairs,urged on by the vain aim of finding their Vindication. These pilgrims disputed in the narrow corridors, hurled dark maledictions, strangled each other on the divine stairways, flung the deceitful books to the bottom of the tunnels, and died as they were thrown into space by men from remote regions. Some went mad . . .The Vindications do exist. I have myself seen two of these books, which were concerned with future people, people who were perhaps not imaginary. But the searchers did not remember that the calculable possibility of a man’s finding his own book, or some perfidious variation of his own book, is close to zero. The clarification of the basic mysteries of humanity – the origin of the Library and of time – was also expected. It is credible that those grave mysteries can be explained in words: if the language of the philosophers does not suffice, the multiform Library will have produced the unexpected language required and the necessary vocabularies and grammars for this language.

It is now four centuries since men have been wearying the hexagons . . .There are official searchers, inquisitors. I have observed them carrying out their functions: they arealways exhausted. They speak of a staircase without steps where they were almost killed. They speak of galleries and stairs with the local librarian. From time to time they will pick up the nearest book and leaf through its pages, in search of infamous words. Obviously, no one expects to discoveranything.The uncommon hope was followed, naturally enough, by deep depression. The certainty that some shelf in some hexagon contained precious books and that these books were inaccessible seemed almost intolerable. A blasphemous sect suggested that all searches be given up and that men everywhere shuffle letters and symbols until they succeeded in composing, by means of an improbable stroke of luck, the canonical books. The authorities found themselves obliged to issue severe orders. The sect disappeared, but in my childhood I still saw old men who would hide out inthe privies for long periods of time, and, with metal disks in a forbidden dicebox, feebly mimic the divine disorder.Other men, inversely, thought that the primary task was to eliminate useless works. They would invade the hexagons, exhibiting credentials which were not always false, skim through a volume with annoyance, and then condemn entire bookshelves to destruction: their ascetic, hygenic fury is responsible for the senseless loss of millions of books. Their name is execrated; but those who mourn the “treasures” destroyed by this frenzy, overlook two notorious facts. One: the Library is so enormous that any reduction undertaken by humans is infinitesimal. Two: each book is unique,irreplaceable, but (inasmuch as the Library is total) there are always several hundreds of thousands of imperfect facsimiles – of works which differ only by one letter or one comma. Contrary to public opinion, I dare suppose that the consequences of the depredations committed by the Purifiers have been exaggerated by the horror which these fanatics provoked. They were spurred by the delirium of storming the books in the Crimson Hexagon: books of a smaller than ordinary format, omnipotent,illustrated, magical.We know, too, of another superstition of that time: the Man of the Book. In some shelf of some hexagon, men reasoned, there must exist a book which is the cipher and perfect compendium of all the rest: some librarian has perused it, and it is analogous to a god. Vestiges of the worship of that remote functionary still persist in the language of this zone. Many pilgrimages have sought Him out.For a century they trod the most diverse routes in vain. How to locate the secret hexagon which harbored it? Someone proposed a regressive approach: in order to locate book A, first consult book B which will indicate the location of A; in order to locate book B, first consult book C, and so onad infinitum . . . I have squandered and consumed my years in adventures of this type. To me, it does not seem unlikely that on some shelf of the universe there lies a total book.

I pray the unknown gods that some man – even if only one man, and though it have been thousands of years ago! – may have examined and read it. If honor and wisdom and happiness are not for me, let them be for others. May heaven exist, though my place be in hell. Let me be outraged and annihilated, but may Thy enormous Library be justified, for one instant, in one being.The impious assert that absurdities are the norm in the Library and that anything reasonable (even humble and pure coherence) is an almost miraculous exception. They speak (I know) of “the febrile Library, whose hazardous volumes run the constant risk of being changed into others and in which everything is affirmed, denied, and confused as by a divinity in delirium.” These words, which not only denounce disorder but exemplify it as well, manifestly demonstrate the bad taste of the speakers and their desperate ignorance. Actually, the Library includes all verbal structures, all the variations allowed by the twenty-five orthographic symbols, but it does not permit of one absolute absurdity.It is pointless to observe that the best book in the numerous hexagons under my administration i entitled Combed Clap of Thunder; or that another is called The Plaster Cramp; and still another Axaxaxas Mlo. Such propositions as are contained in these titles, at first sight incoherent, doubtless yield a cryptographic or allegorical justification. Since they are verbal, these justifications already figure, ex hypothesi, in the Library. I can not combine certain letters, as dhcmrlchtdj, which the divine Library has not already foreseen in combination, and which in one of its secret languages does not encompass some terrible meaning. No one can articulate a syllable which is not full of tenderness and fear, and which is not, in one of those languages, the powerful name of some god. To speak is to fall into tautologies. This useless and wordy epistle itself already exists in one of the thirty volumes of the five shelves in one of the uncountable hexagons – and so does its refutation. (An number of possible languages makes use of the same vocabulary; in some of them, the symbol library admits of the correct definition ubiquitous and everlasting system of hexagonal galleries, but library is bread or pyramid or anything else, and the seven words which define it possess another value.

You who read me, are you sure you understand my language? Methodical writing distracts me from the present condition of men. But the certainty that everything has been already written nullifies or makes phantoms of us all. I know of districts where the youth prostrate themselves before books and barbarously kiss the pages, though they do not know how to make out a single letter. Epidemics, heretical disagreements, the pilgrimages which inevitably degenerate into banditry, have decimated the population. I believe I have mentioned the suicides,more frequent each year. Perhaps I am deceived by old age and fear, but I suspect that the human species – the unique human species – is on, the road to extinction, while the Library will last on forever: illuminated, solitary, infinite, perfectly immovable, filled with precious volumes, useless,incorruptible, secret.Infinite I have just written. I have not interpolated this adjective merely from rhetorical habit. It isnot illogical, I say, to think that the world is infinite. Those who judge it to be limited, postulate that in remote places the corridors and stairs and hexagons could inconceivably cease – a manifest absurdity. Those who imagined it to be limitless forget that the possible number of books is limited.I dare insinuate the following solution to this ancient problem: The Library is limitless and periodic.If an eternal voyager were to traverse it in any direction, he would find, after many centuries, that the same volumes are repeated in the same disorder (which, repeated, would constitute an order: Order itself).

My solitude rejoices in this elegant hope. The original manuscript of the present note does not contain digits or capital letters. The punctuation is limited to the comma and the period. These two signs, plus the space sign and the twenty-two letters of the alphabet, make up the twenty-five sufficient symbols enumerated by the unknown author.  Formerly, for each three hexagons there was one man. Suicide and pulmonary diseases have destroyed this proportion. My memory recalls scenes of unspeakable melancholy: there have been many nights when I have ventured down corridors and polished staircases without encountering a single librarian.  I repeat: it is enough that a book be possible for it to exist. Only the impossible is excluded.For example: no book is also a stairway, though doubtless there are books that discuss and deny and demonstrate this possibility and others whose structure corresponds to that of s stairway. Letizia Alvarez de Toledo has observed that the vast Library is useless. Strictly speaking, one single volume should suffice: a single volume of ordinary format, printed in nine or ten type body,and consisting of an infinite number of infinitely thin pages. (At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Cavalieri said that any solid body is the superposition of an infinite number of planes.) This silky vade mecum would scarcely be handy: each apparent leaf of the book would divide into other analogous leaves. The inconceivable central leaf would have no reverse.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User-generated_content

User-generated content (UGC) is defined as “any form of content such as blogs, wikis, discussion forums, posts, chats, tweets, podcasting, pins, digital images, video, audio files, and other forms of media that was created by users of an online system or service, often made available via”.[1] It entered mainstream usage during 2005,[2] having arisen in web publishing and new media content production circles. It is used for a wide range of applications, including problem processing, news, gossip and research and reflects the expansion of media production through new technologies that are accessible and affordable to the general public. In addition to the above-mentioned technologies, user-generated content may also employ a combination of open source, free software, and flexible licensing or related agreements to further reduce the barriers to collaboration, skill-building and discovery (“‘UGC'”) has also gained in popularity over the last decade, as more and more users have begun to flock to social media and “‘content-based'” sharing sites.[citation needed]

Sometimes UGC can constitute only a portion of a website. For example, there are sites where the majority of content is prepared by administrators, but numerous user reviews of the products being sold are submitted by regular users of the site.

Often UGC is partially or totally monitored by website administrators to avoid offensive content or language, copyright infringement issues, or simply to determine if the content posted is relevant to the site’s general theme.

However, there has often been little or no charge for uploading user-generated content. As a result, the world’s data centers are now replete with exabytes of UGC that, in addition to creating a corporate asset,[3] may also contain data that can be regarded as a liability.[4][5]

Contents

1 General requirements

2 Adoption and recognition by mass media

3 Motivation and incentives

4 Types of user-generated content

5 New business models

6 Criticism

7 Legal problems related to UGC

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

General requirements

The advent of user-generated content marked a shift among media organizations from creating online content to providing facilities for amateurs to publish their own content.[citation needed]

User generated content has also been characterized as Citizen Media as opposed to the ‘Packaged Goods Media’ of the past century.[6] Citizen Media is audience-generated feedback and news coverage.[7] People give their reviews and share stories in the form of user-generated and user-uploaded audio and user-generated video.[8] The former is a two-way process in contrast to the one-way distribution of the latter. Conversational or two-way media is a key characteristic of so-called Web 2.0 which encourages the publishing of one’s own content and commenting on other people’s.

The role of the passive audience therefore has shifted since the birth of New Media, and an ever-growing number of participatory users are taking advantage of the interactive opportunities, especially on the Internet to create independent content. Grassroots experimentation then generated an innovation in sounds, artists, techniques and associations with audiences which then are being used in mainstream media.[9] The active, participatory and creative audience is prevailing today with relatively accessible media, tools and applications, and its culture is in turn affecting mass media corporations and global audiences.

The OECD has defined three central schools for UGC:[10]

Publication requirement: While UGC could be made by a user and never published online or elsewhere, we focus here on the work that is published in some context, be it on a publicly accessible website or on a page on a social networking site only accessible to a select group of people (e.g., fellow university students). This is a useful way to exclude email, two-way instant messages and the like.

Creative effort: Creative effort was put into creating the work or adapting existing works to construct a new one; i.e. users must add their own value to the work. UGC often also has a collaborative element to it, as is the case with websites which users can edit collaboratively. For example, merely copying a portion of a television show and posting it to an online video website (an activity frequently seen on the UGC sites) would not be considered UGC. If a user uploads his/her photographs, however, expresses his/her thoughts in a blog, or creates a new music video, this could be considered UGC. Yet the minimum amount of creative effort is hard to define and depends on the context.

Creation outside of professional routines and practices: User generated content is generally created outside of professional routines and practices. It often does not have an institutional or a commercial market context. In extreme cases, UGC may be produced by non-professionals without the expectation of profit or remuneration. Motivating factors include: connecting with peers, achieving a certain level of fame, notoriety, or prestige, and the desire to express oneself.

Today, brands of all sizes are eager to jump into the UGC/social networking environment. But doing so blindly—without clear objectives in mind—can lead to an unsatisfying experience. Many companies may ask you to post your reviews or comments freely to their Facebook page. This could end up disastrous if a user makes a comment that steers people away from the product. As with any new environment, it’s important first to understand where you want to go and how you can get there before diving in.[11]

Mere copy & paste or hyperlinking could also be seen as user generated self-expression. The action of linking to a work or copying a work could in itself motivate the creator, express the taste of the person linking or copying. Digg.com, StumbleUpon.com, and leaptag.com are good examples of where such linkage to work happens. The culmination of such linkages could very well identify the tastes of a person in the community and make that person unique

Adoption and recognition by mass media

The BBC set up a user generated content team as a pilot in April 2005 with 3 staff. In the wake of the 7 July 2005 London bombings and the Buncefield oil depot fire, the team was made permanent and was expanded, reflecting the arrival in the mainstream of the citizen journalist.[citation needed] After the Buncefield disaster the BBC received over 5,000 photos from viewers. The BBC does not normally pay for content generated by its viewers.

In 2006 CNN launched CNN iReport, a project designed to bring user generated news content to CNN. Its rival Fox News Channel launched its project to bring in user-generated news, similarly titled “uReport”. This was typical of major television news organisations in 2005–2006, who realised, particularly in the wake of the London 7 July bombings, that citizen journalism could now become a significant part of broadcast news.[12][citation needed] Sky News, for example, regularly solicits for photographs and video from its viewers.

User-generated content was featured in Time magazine’s 2006 Person of the Year, in which the person of the year was “you”, meaning all of the people who contribute to user generated media such as YouTube and Wikipedia.[13] The precursor to user-generated content uploaded on YouTube was America’s Funniest Home Videos.[14]

Motivation and incentives

While the benefit derived from user generated content for the content host is clear, the benefit to the contributor is less direct. There are various theories behind the motivation for contributing user generated content, ranging from altruistic [1], to social, to materialistic. Due to the high value of user generated content, many sites use incentives to encourage their generation. These incentives can be generally categorized into implicit incentives and explicit incentives.[15]

Implicit incentives: These incentives are not based on anything tangible. Social incentives are the most common form of implicit incentives. These incentives allow the user to feel good as an active member of the community. These can include relationship between users, such as Facebook’s friends, or Twitter’s followers. Social incentives also include the ability to connect users with others, as seen on the sites already mentioned as well as sites like YouTube, which allow users to share media from their lives with others. Other common social incentives are status, badges or levels within the site, something a user earns when they reach a certain level of participation which may or may not come with additional privileges. Yahoo! Answers is an example of this type of social incentive. Social incentives cost the host site very little and can catalyze vital growth; however, their very nature requires a sizable existing community before it can function.

Explicit incentives: These incentives refer to tangible rewards. Examples include financial payment, entry into a contest, a voucher, a coupon, or frequent traveler miles. Direct explicit incentives are easily understandable by most and have immediate value regardless of the community size; sites such as the Canadian shopping platform Wishabi and Amazon Mechanical Turk both use this type of financial incentive in slightly different ways to encourage user participation. The drawback to explicit incentives is that they may cause the user to be subject to the overjustification effect, eventually believing the only reason for the participating is for the explicit incentive. This reduces the influence of the other form of social or altruistic motivation, making it increasingly costly for the content host to retain long-term contributors.[16]

Types of user-generated content

There are many types of user-generated content: Internet forums, where people talk about different topics; blogs are services where users can post about many topics, the most important blog services are these: Blogger, Tumblr and WordPress.There are also wikis, where every anonymous user can edit and make changes as, for example, at Wikipedia or Wikia. Another type of user-generated content are social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or VK, where users interact with other people chatting, writing messages or posting images or links. Companies like YouTube are enticing a growing number of users to not only consume the content, but to create it as well.

Other types of this content are fanfiction like FanFiction.Net, imageboards; various works of art, as with deviantArt and Newgrounds; mobile photos and video sharing sites such as Picasa and Flickr; customer review sites; audio social networks such as SoundCloud; crowd funding, like Kickstarter; or crowdsourcing.

Video games have an additional form of user-generated content, namely mods. Some games come with level editor programs to aid in their creation. Most of these only appear in single-player games, but some multiplayer games also have them. A few massively multiplayer online role-playing games including Star Trek Online, Second Life, and EverQuest 2 have UGC systems integrated into the game itself.[17]

A popular use of UGC involves collaboration between a brand and a user. For example, the “Elf Yourself” videos by Christmas Jib Jab that come back every year around Christmas. The Jib Jab website lets people use their photos of friends and family that they have uploaded to make a holiday video to share across the internet. You cut and paste the faces of the people in the pictures to animated dancing elves.[18]

Some bargain hunting sites feature user-generated content, such as Dealsplus, Slickdeals, and FatWallet which allow users to post, discuss, and control which bargains get promoted within the community. Because of the dependency of social interaction, these sites fall into the category of social commerce.

New business models

The media companies of today are starting to realize that the users themselves can create plenty of material that is interesting to a broader audience and adjust their business models accordingly. Many young companies in the media industry, such as YouTube and Facebook, have foreseen the increasing demand of UGC, whereas the established, traditional media companies have taken longer to exploit these kinds of opportunities.

Big and small brands are attempting to lure customers and potential customers back to their websites with rich social experiences, like the photo- and video-sharing that has made networks like Vine and Instagram so popular.[19] Realizing the demand for UGC is more about creating a “playing field†for the visitors rather than creating material for them to consume. A parallel development can be seen in the video game industry, where games such as World of Warcraft, The Sims and Second Life give the player a large amount of freedom so that essential parts of the games are actually built by the players themselves.

Criticism

Question book-new.svg

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2009)

The term “user-generated content” has received some criticism. The criticism to date has addressed issues of fairness, quality[citation needed], privacy[citation needed], the sustainable availability of creative work and effort among legal issues namely related to intellectual property rights such as copyrights etc.

Some commentators assert that the term “user” implies an illusory or unproductive distinction between different kinds of “publishers”, with the term “users” exclusively used to characterize publishers who operate on a much smaller scale than traditional mass-media outlets or who operate for free.[20] Such classification is said to perpetuate an unfair distinction that some argue is diminishing because of the prevalence and affordability of the means of production and publication. A better response[according to whom?] might be to offer optional expressions that better capture the spirit and nature of such work, such as EGC, Entrepreneurial Generated Content (see external reference below).[citation needed]

Sometimes creative works made by individuals are lost because there are limited or no ways to precisely preserve creations when a UGC Web site service closes down. One example of such loss is the closing of the Disney massively multiplayer online game “VMK”. VMK, like most games, has items that are traded from user to user. Many of these items are rare within the game. Users are able to use these items to create their own rooms, avatars and pin lanyard. This site shut down at 10 pm CDT on 21 May 2008. There are ways to preserve the essence, if not the entirety of such work through the users copying text and media to applications on their personal computers or recording live action or animated scenes using screen capture software, and then uploading elsewhere. Long before the Web, creative works were simply lost or went out of publication and disappeared from history unless individuals found ways to keep them in personal collections.[citation needed]

Another criticized aspect is the vast array of user-generated product and service reviews that can at times be misleading for consumer on the web. A study conducted at Cornell University found that an estimated 1 to 6 percent of positive user-generated online hotel reviews are fake.[21]

Content creation will continue to grow, and content consumption driven by the growth of mobile devices and OTT video screens will grow as well. Which moves the challenges from creation to curation. Curation is the driving force that provides contextually relevant video content in channelized environment. And for brands looking for a way to contextualize and validate their native video content creation, the emergence of Native Channels can’t come soon enough.[22]

Legal problems related to UGC

The ability for services to accept user-generated content opens up a number of legal concerns: depending on local laws, the operator of a service may be liable for the actions of its users. In the United States, the “Section 230” exemptions of the Communications Decency Act state that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This clause effectively provides a general immunity for websites that host user-generated content that is defamatory, deceptive or otherwise harmful, even if the operator knows that the third-party content is harmful and refuses to take it down. An exception to this general rule may exist if a website promises to take down the content and then fails to do so.[23]

Copyright laws also play a factor in relation to user-generated content, as users may use such services to upload works—particularly videos—that they do not have the sufficient rights to distribute. In many cases, the use of these materials may be covered by local “fair use” laws, especially if the use of the material submitted is transformative.[24] Local laws also vary on who is liable for any resulting copyright infringements caused by user-generated content; in the United States, the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act (OCILA)—a portion of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), dictates safe harbor provisions for “online service providers” as defined under the act, which grants immunity from secondary liability for the copyright-infringing actions of its users. However, to qualify for the safe harbors, the service must promptly remove access to alleged infringing materials upon the receipt of a notice from a copyright holder or registered agent, and the service provider must not have actual knowledge that their service is being used for infringing activities.[25][26] The European Union’s approach is horizontal by nature, which means that civil and criminal liability issues are addressed under the Electronic Commerce Directive. Section 4 deals with liability of the ISP while conducting “mere conduit” services, caching and web hosting services.[27]

See also

Carr-Benkler wager

Collective intelligence

Communal marketing

Consumer generated marketing

Creative Commons

Crowdsourcing

Customer engagement

Fan art

Fan Fiction

Modding

Networked information economy

Participatory design

User innovation

User-generated TV

Web 2.0

Anonymous