editor

This is my drawing – and this observant blogger discovered

something interesting enough:

She says:

From

http://iiiinspired.blogspot.com/2013/07/a-little-this-and-that-art-vs-dress.html

ABOUT THE “QUOTE”

“good artists borrow – great artists steal”

Gold Stick

Purpleheart sawdust on porch – photo document.

FRENCH HORN

TRUMPET

TRUMPET

TUBA

TUBA

PETER SHIRE : CUPS from ERIC MINH SWENSON on Vimeo.

Little Piece of Paradise:

Etymology and semasiology

The word “paradise” entered English from the French paradis, inherited from the Latin paradisus, from Greekparádeisos (παÏάδεισος), and ultimately from an Old Iranian root, attested in Avestan as pairi.daêza-.[1] The literal meaning of this Eastern Old Iranian language word is “walled (enclosure)”,[1] from pairi- “around” + -diz “to create (a wall)”.[2] The word is not attested in other Old Iranian languages (these may however be hypothetically reconstructed, for example as Old Persian *paridayda-).

By the 6th/5th century BCE, the Old Iranian word had been adopted as Akkadian pardesu and Elamite partetas, “domain”. It subsequently came to indicate walled estates, especially the carefully tended royal parks and menageries. The term eventually appeared in Greek as parádeisos “park for animals” in the Anabasis of the early 4th century BCE Athenian gentleman-scholar Xenophon. Aramaic pardaysa similarly reflects “royal park”.

Hebrew פרדס (pardes) appears thrice in the Tanakh; in the Song of Solomon 4:13, Ecclesiastes 2:5 and Nehemiah 2:8. In those contexts it could be interpreted as an “orchard” or a “fruit garden”.

In the 3rd–1st centuries BCE Septuagint, Greek παÏάδεισος (parádeisos) was used to translate both Hebrew pardesand Hebrew gan, “garden”: it is from this usage that the use of “paradise” to refer to the Garden of Eden derives. The same usage also appears in Arabic and in theQuran as Ùردوس (firdaws).

The idea of a walled enclosure was not preserved in most Iranian usage, and generally came to refer to a plantation or other cultivated area, not necessarily walled. For example, the Old Iranian word survives in New Persian pÄlÄ«z (or “jÄlÄ«z”), which denotes a vegetable patch. However, the word park, as well as the similar complex of words that have the same indoeuropean root: garden, yard, girdle, orchard, court, etc., all refer simply to a deliberately enclosed area, but not necessarily an area enclosed by walls.

For the connection between these ideas and that of the city, compare German Zaun (“fence”), English town and Dutch tuin (“garden”), or garden/yard with Nordicgarðr and Slavic gard (both “city”).

CP Black Photographs P2 | Just Published on Rectangular Objects

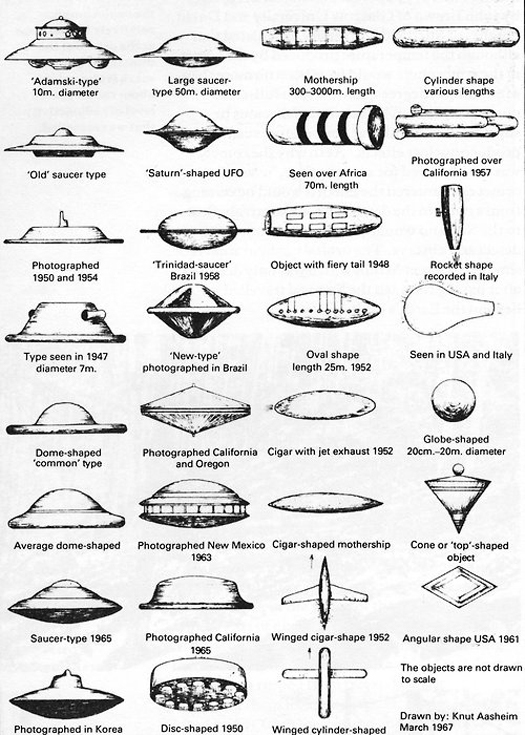

Empirical and conceptual objects

|

Non-motivated functions of art The non-motivated purposes of art are those that are integral to being human, transcend the individual, or do not fulfill a specific external purpose. In this sense, Art, as creativity, is something humans must do by … KEEP GOING >>>

BOC’s favorite oracle

another link to the Eye of the Duck